What Has the Us Done to Oppress Hispanics

SAN ANTONIO — When Texas leaders canonical a tough new immigration enforcement police force known equally SB4, they did so in a state that has had a long, continuing and sometimes unacknowledged struggle for disinterestedness by the country'due south residents of Mexican descent.

That struggle has existed since before Texas became a state and has ranged from mob violence and massacres — some perpetrated by the Texas Rangers — to voting and employment discrimination and school and housing segregation. More recently, courts have alleged the state's voter ID law and redistricting maps discriminatory.

Related: Texas' SB4 Immigration Enforcement Police force: 5 Things to Know

Supporters of SB4 cramp at suggestions the immigration enforcement law may foster racism or encourage discrimination, but as they try to enact information technology on Sept. i, information technology will be incommunicable to ignore the state'due south history of racism and the electric current challenges for Texans of Mexican descent.

"This is a step backwards in terms of having Mexican-Americans thought of as really U.S. citizens, every bit opposed to foreigners rather than interlopers."

Consider that, during the period from 1848 to 1928, at least 232 people of Mexican descent were killed by mob violence or lynchings in Texas — some committed at the easily of Texas Rangers, according to research past William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb, authors of "Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Confronting Mexicans in the United States." Texas led 12 states in killings of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, the authors solidly documented.

In add-on, the effort to place Texas nether the anti-discrimination provisions of the Voting Rights Act was the genesis of the 1975 expansion of the act to extend its protections of voting rights of Latinos and other people who were then called "language minorities."

More recently, Texas' voter ID law, enacted in 2013, has been struck down in a series of courtroom decisions that found it discriminatory.

Also, Texas' education board but added Mexican-American studies as an elective course to its public schoolhouse curriculum in 2014.

Related: Estimate Again Finds Bigotry in Texas Voter ID Law

"For Texas it really has been a dull march to effective citizenship for Mexican-Americans," said John Morán González, manager of the Center for Mexican American Studies at Academy of Texas at Austin.

González is ane of the founders of the Refusing to Forget Project, which documented and created an exhibit for the Bullock Texas Country History Museum on country-sanctioned violence confronting Mexicans and Mexican-Americans living on the Texas-Mexico border during 1910-20. Thousands were killed during that menses.

The grouping touts its project'due south mission as educating people virtually a forgotten period to "raise the profile of a struggle for justice and ceremonious rights that continues to influence social relationships today."

There's no uncertainty Mexican-Americans have fabricated great strides in Texas, where Latinos brand up forty percent of the state population and are overwhelmingly of Mexican descent.

But historians and ceremonious rights activists see a thread of historical racism and discrimination running through the implementation of SB4.

"This is a step backwards in terms of having Mexican-Americans idea of every bit really U.South. citizens, equally opposed to foreigners rather than interlopers," González said.

Thomas Saenz, president and CEO of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), a civil rights legal group, is more blunt. "This law has racism written all over it," he said.

MALDEF, started in San Antonio, has been at the heart of many of the land'southward Mexican American population's fights for equity. Information technology represented the Edgewood Contained School Commune, a poorer in San Antonio, when the district challenged the state'south public school financing system every bit discriminatory against poorer students, many of whom were Mexican-American or Latino.

The lawsuit led to an overhaul of the funding organization. Years later state lawmakers are again trying to refashion the funding formulas for the country'southward approximately v 1000000 schoolchildren who are 52 percent Latino.

When MALDEF sued the state in 1987, just x per centum of state funds for public universities went to the edge region and Southward Texas, where many of the state's residents of Mexican descent live. The region also had but two doctoral programs. The adapt led to state legislation to beef upward higher education in the edge region.

"I do retrieve there has been a continuous theme of 'Mexican-Americans don't deserve the same things everybody else has' by the powerful," said Al Kauffman, a former MALDEF attorney who litigated the teaching cases and is now a professor at St. Mary's Academy School of Law in San Antonio. "People are looking for means to command the population."

Related: San Antonio Sues Texas Over SB4 Immigration Law

The organization is continuing its office of contesting the country in court on behalf of Latinos. On Thursday, it filed suit on behalf of the urban center of San Antonio, three non-turn a profit groups and a San Antonio City Council member to foreclose SB4 from taking effect.

Saenz and plaintiffs in the case warned that the law volition permit every law enforcement officeholder, booking agent and other constabulary enforcement figures to "decide on their ain without any guidance or restrictions from their duly elected and appointed superiors, police chiefs, sheriffs and elected officials ... whether and how to enforce federal clearing constabulary."

Such "unfettered" and "arbitrary" policing will atomic number 82 to discrimination confronting Latinos and other minorities, regardless of their citizenship or immigration status, he said.

The struggles of Texans of Mexican descent take been and so many they take made the state the birthplace of several Latino civil rights groups. In addition to MALDEF, some of those groups are the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, formed to protect voting rights of Mexican Americans. The League of United Latin American Citizens, or LULAC, was started in 1929 to fight the entrenched racism of the time and the American GI Forum was founded in 1948 to button for equal treatment for WWII Mexican-American veterans.

Racial Profiling Versus Immigration Enforcement

The dividing lines over SB4 are not as neat equally white versus Latino. Texas has long had a meaning Latino contingent willing to back tough measures on illegal immigration and edge security.

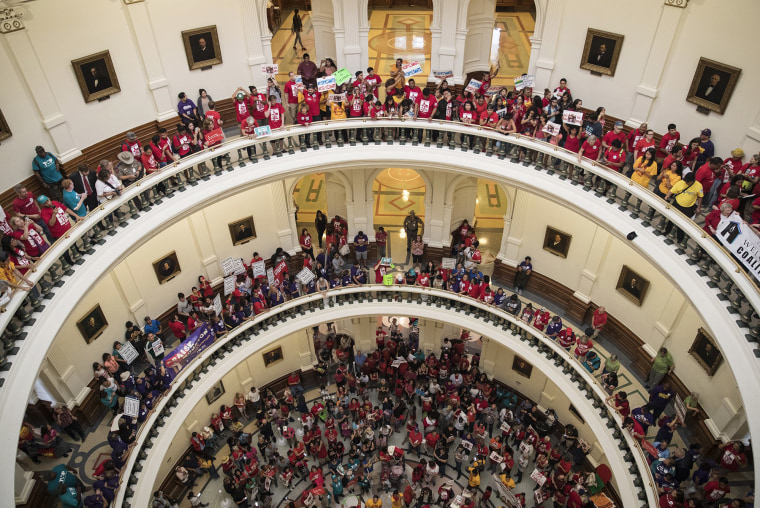

But the acrimony SB4 is stoking and its potential for causing racial clashes was visible Mon when GOP land Rep. Matt Rinaldi of Irving, Texas, said in social media and told Mexican American Democratic legislators that he called Immigration and Customs Enforcement on people protesting SB4 at the Capitol. Many protesters were Latino and some held signs that read, "I'm illegal and I'1000 here to stay."

Rindaldi's call — which Water ice has said it is unaware of receiving — led to a shouting match, a well-nigh brawl and accusations of threats of violence from both sides.

Related: Texas Lawmakers Charge Each Other of Set on, Threats As Hundreds of 'SB4' Protesters Disrupt Session

Defending the Mexican-American lawmakers' response to Rinaldi, state Rep. Cesar Blanco, an El Paso, Texas, Democrat, wrote in in the Texas Tribune: "This isn't about decorum. I'grand a crewman; I tin can take the salty language. This is about whether we sit idly or stand up up in the face of ethnic scapegoating, racial profiling and abusing the power of the country to intimidate the less powerful."

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has trumpeted the law every bit a tool for public safety and one that will stop so-called sanctuary cities, municipalities that regulate their law officers' enforcement of federal immigration laws and cooperation with federal immigration authorities. Opponents of such restrictions say cities release criminals that they should detain until they tin be put in displacement and that puts public safety at hazard.

SB4 allows for criminal penalties of upwardly to $25,000 a day and removal from part of public officials, police force chiefs, sheriffs and others who defy the law.

"Texans await us to go on them safe and that is exactly what we are going to do by me signing this law," Abbott said before he signed SB4 live on Facebook. He told NBC Nightly News that he knows the Latino community needs to experience it has nothing to fear from the new constabulary because his wife and family are Hispanic.

"The simply people who face any blazon of event are criminals ... We included in the law a ban on racial profiling, making it illegal," Abbott said.

A mean solar day after the police was signed, Texas sued MALDEF along with Austin's mayor and city quango members and the Travis County sheriff for beingness "hostile" to federal immigration enforcement officers and not cooperating with them, even though SB4 doesn't go into outcome until Sept. 1.

In a column written with two Latino police enforcement leaders — Victor Rodriguez, police main in McAllen and J.Eastward. "Eddie" Guerra, sheriff in Hidalgo County in the Rio Grande Valley — Abbott asserted the law won't change how law enforcement already works in Texas and would merely subject criminals to questioning almost their status and condemned opponents.

"Whether driven by misunderstanding or by purposeful fear mongering, those who are inflaming unrest, place all who alive in Texas at greater risk," they stated in the cavalcade that Abbot said drew back up from an additional 23 law enforcement officers, almost all Latino, later on information technology was published.

However, the Texas Police Chiefs Association opposed SB4 while it made its manner through Texas' Republican-controlled Legislature. The constabulary also has fatigued fervent opposition from a number of Latino leaders, lawmakers, organizations and residents.

"It's besides like shooting fish in a barrel to racially profile [under SB4]. What is reasonable suspicion? Is it nervousness?" said Mario H. Lopez, president of the Hispanic Leadership Fund, a politically center-right arrangement that focuses on Latinos.

"If I'm jaywalking and I'm a U.S. citizen and I encounter a cop coming towards me, I might starting time thinking, what'due south going on now?" Lopez said. "If a cop sees me equally suspicious because I'm nervous, will I be detained?"

Is Bigotry Part of Texas' Identity?

Carrigan and Webb, the authors who documented mob violence confronting Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, debate in their book that "uncovering the forgotten expressionless murdered by Anglo lynch mobs is therefore, less of a reopening of one-time wounds than a ways to enhance mutual understanding in a nation where race remains ane of the deepest fault lines."

That can as well apply to the debate over SB4, Carrigan said.

"My guess is at that place is a white perception and Mexican (and Mexican-American) perception" of SB4, he said. White Texans likely think it'southward not deeply racist, merely Texans of Mexican origin have a "longer, historical framework for understanding information technology: The Texas governor and Texas officers have not been a forcefulness we tin trust for many, many years and we are going to view that in that context, with the lynchings and Texas Rangers in the groundwork," he said.

Luis Fraga, co-director of the Institute of Latino Studies at the University of Notre Dame, said what is happening with SB4, along with Texas' recently toughened voter laws, "has to be understood in the context of what Texas has e'er been."

Following the state's revolution, Mexican Texans were soon excluded from "whatever meaningful place in the politics of Texas," Fraga said. White settlers who were invited to Texas came from the South and brought with them their understanding of social relations between the races, he said.

Fraga points to Alamo defender and political leader Juan Seguín, who fought for Texas independence. Later on Texas became a republic, Seguín became mayor of San Antonio, only he was chased out past a white mob that thought he was colluding with Mexico. He had to abscond to Mexico where he was considered a traitor, said Fraga who uses Seguín's story in his class teaching leadership on issues important to the future of U.S. Latino communities.

"This marginalization and bigotry against people of Mexican origin," Fraga said, "is at the centre of Texas' identity."

Follow NBC News Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/history-racism-against-mexican-americans-clouds-texas-immigration-law-n766956